Christ's Descent into Hades After the Crucifixion and Why it Matters

Holy Saturday in the Orthodox Christian Church

I grew up in a Christian family – one of those families that was at Church every time the doors were open. On Sunday mornings we attended Sunday school followed by a service featuring praise songs and a ~30-minute sermon; Sunday evenings we participated in youth group or the evening service; Wednesday evenings we had kids club – or choir practice if you had aged out of the latter. One day every year, we would add a Friday to the mix: Good Friday. The service would typically include a number of somber hymns, a large bodiless cross, and a short sermon reflecting on the crucifixion – and sometimes communion.1 Afterward, we would go home, eat dinner, and enjoy the rest of our weekend, which would consist of a Church-wide Easter morning breakfast followed by a celebratory service with the call-and-response: “He is risen! Indeed he is risen!”

We had Good Friday. We had Easter Sunday. But we did not have a Holy Saturday.

HOLY SATURDAY IN THE ORTHODOX CHURCH

In the Orthodox Church, Holy Saturday is the day we remember Christ’s descent into Hades; it is preceded by a full week of services remembering events such as the resurrection of Lazarus (Saturday before Holy Saturday), Christ’s entrance into Jerusalem (Palm Sunday), the last supper, the crucifixion (on Holy Thursday in anticipation of Holy Friday), placement of his body in the tomb (Holy Friday afternoon), and the Lamentations (Holy Friday evening in anticipation of Holy Saturday). Following the Lamentations, the faithful hold vigil by the tomb of Christ. They chant the Psalms, read the Gospel accounts, and wait, with mounting expectation, for the his resurrection. This continues all night until the beginning of Divine Liturgy on Holy Saturday morning.

CHRIST’S DESCENT INTO HELL OR HADES?

I recall wondering as a kid what happened to the soul of Christ in the interim between the crucifixion and the resurrection. But this was not a topic my non-denominational Christian confession was equipped to handle. My inquiries were met with hemming and hawing – if not the claim that the Bible did not teach it so we did not believe it. So imagine my surprise when I discovered that the Bible actually has a lot to say about it, as it is an important theme to the entire Christian narrative.

Hades vs. Hell

To get to the heart of Christ’s descent into hell and its importance in our faith, we must first examine two distinct words: hades and gehenna.

Hades (Gr. ᾅδης) is used in the Old (Heb. שְׁאול) and New Testaments to refer to the temporary abode of the souls of the dead. Often transliterated (sheol) or rendered grave or pit in the Old Testament (Psalm 88:3, 5), sheol is said to have an insatiable appetite to swallow the living (Proverbs 1:12; 27:20); it inprisons the souls of both the righteous and the wicked (Ecclesiastes 2:9–10), who cannot pass back through its locked gates (Job 17:16; Isa. 38:10). But as the divine economy progressed in time, God reveals through his Prophet Isaiah that he himself will swallow up death (Isaiah 25:8) and the dead will live (Isaiah 26:19).

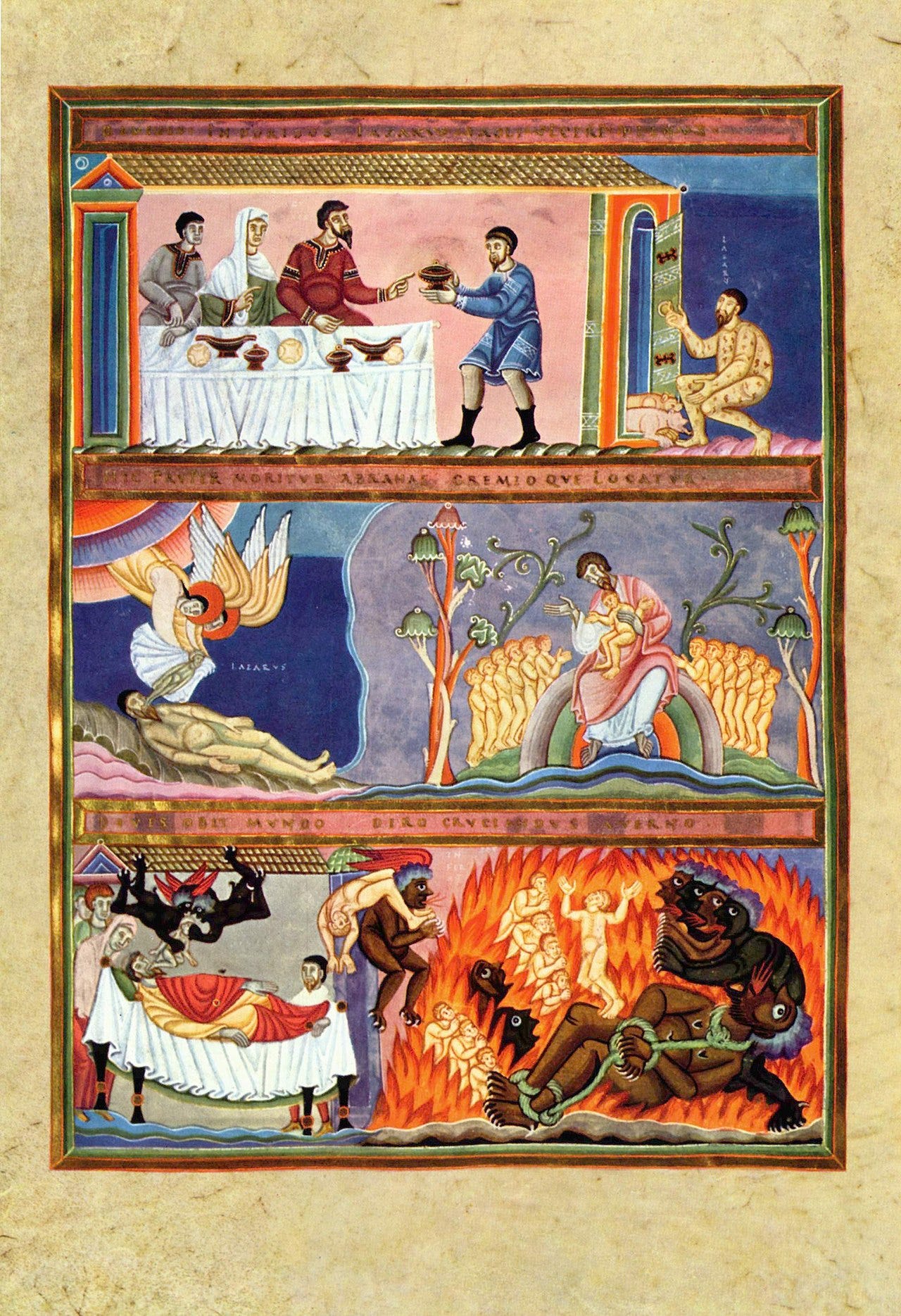

In the New Testament, hades is often rendered hell in older translations (KJV, Douay-Rheims, Websters versions) which only amplifies confusion. The parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus in Luke 16 describes the varying conditions of hades; for the wicked it is a place of torment, for the righteous it is a comfort (Abraham’. In Acts 2:27, the Apostle Peter recalls the words of David in Psalm 16:10: “Thou wilt not leave my soul in hades, neither wilt thou suffer thine holy one to see corruption.” Peter goes on to explain that, “He [David] seeing this before spake of the resurrection of Christ, that his soul was not left in hades, neither his flesh did see corruption” (Acts 2:31). Christ comments to Peter that the gates of hades will not prevail against the Church (Matthew 16:18) – and elsewhere, in Revelation, Christ claims to hold the keys of hades and death (Revelation 1:18).

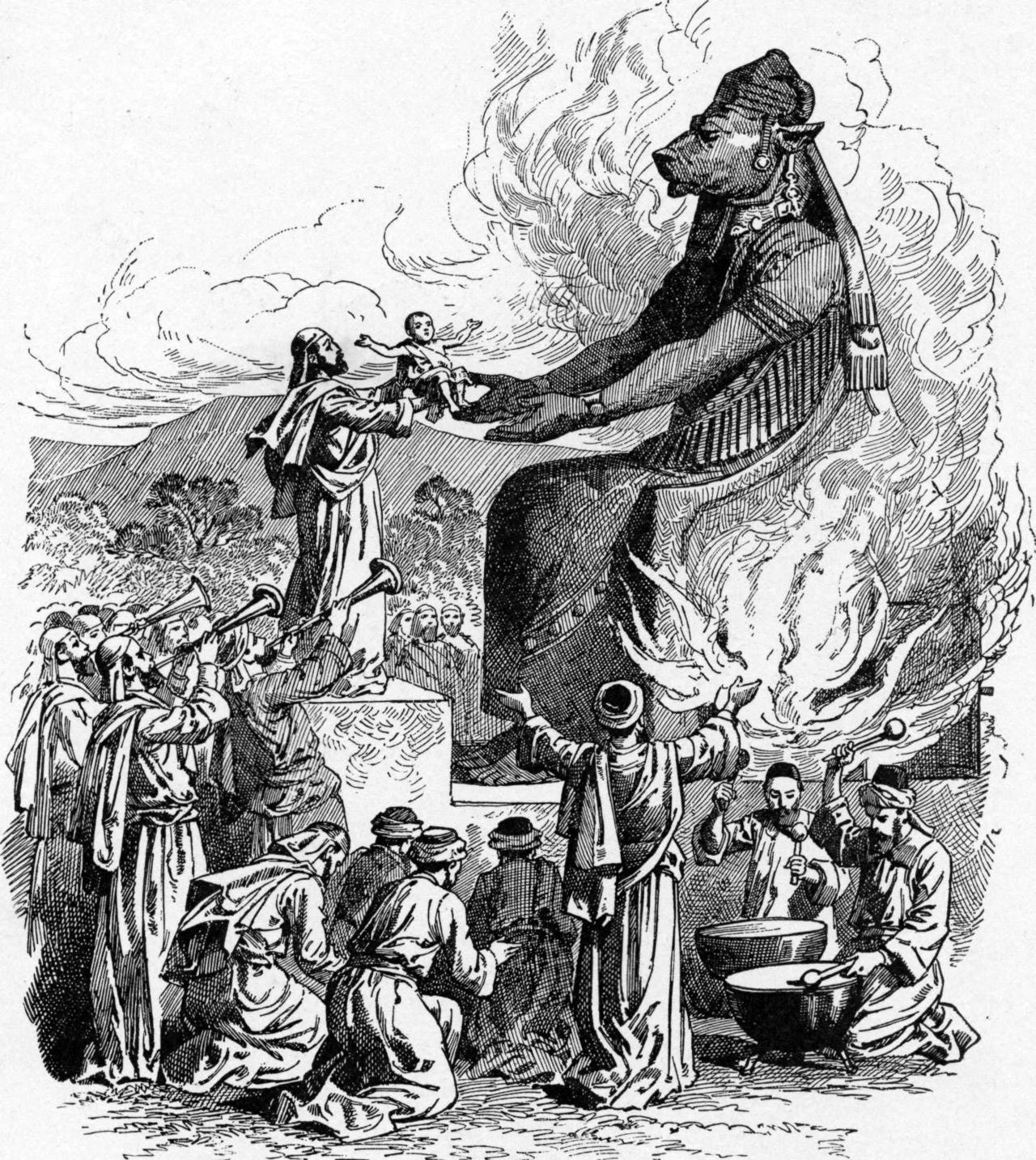

Hell (Gr. γέεννα, gehenna) is a word that comes from the Hebrew ge hinnom (יא בֶן־הִנֹּם,) which refers to a specific geographic location southeast of the old city of Jerusalem known as the valley of hinnom where children were sacrificed by fire to moloch (see Jeremiah 7:31-32; 32:35; 2 Kings 23:10; 2 Chronicles 28:3; 33:6). The idea was that by sacrificing their children to moloch they would receive back fruitfulness of the womb and financial sucess. In Christ’s day, the valley was referenced as a place of torment – idiomatically similar to what we might call a dumpster fire.2

In the New Testament, Christ refers to hell as a place or state where individuals exist in body and soul after the resurrection of the body and the final judgment (Matthew 23:33; 5:29, 30; 10:28). Connecting the idea of gehenna as a place of sacrifice to false gods (demons) with the sacrificial dichotomy Christ places before his listeners in Matthew 9 (sacrifice the entire body to hell or sacrifice that which causes you to sin) provides interesting insight; while a physical place plagued by a history of human sacrifice, the valley of hinnom appears to represent in symbol the place we descend when we sin. In a sense, when we descend the slope of temptation and walk into the valley of sin, we sacrifice ourselves to the evil one in our vain pursuit of worldly success or pleasure (see Matthew 9:43–47). This is how we willingly choose to bear the mark of the beast, as outlined in the recent article on The Apocalypse of Saint John.

IN SUM:

Although hades is occasionally translated in English as hell, the Greek words hades and gehenna (hell) are distinct.

Hades is the temporary abode of the dead; it is what is understood in mythology as the underworld. Ones state in hades, be it of torment or comfort, is a direct result of what the Orthodox Church refers to as the particular judgment which the soul undergoes on the 40th day after separation from the body – and for which reason the Church remembers and prays for the departed. While the particular judgment is understood to be a foretaste of the judgment to come, Orthodox Christians pray that the Lord will grant the departed, “rest…in a place of brightness, a place of refreshment, a place of repose, where all sickness, sighing, and sorrow have fled away.”3 There are inded many documented cases wherein the souls of those in hades have been aided by such prayers – stories that come to us from the visions of saints.4

Hell is the place of eternal torment – often equated with the lake of fire – that was prepared for Satan and his angels; it is where the wicked descend after the final judgment which takes place after the bodily resurrection (Revelation 20:13). Both hades and death are said to be cast there also at the end of the age (Revelation 20:14).

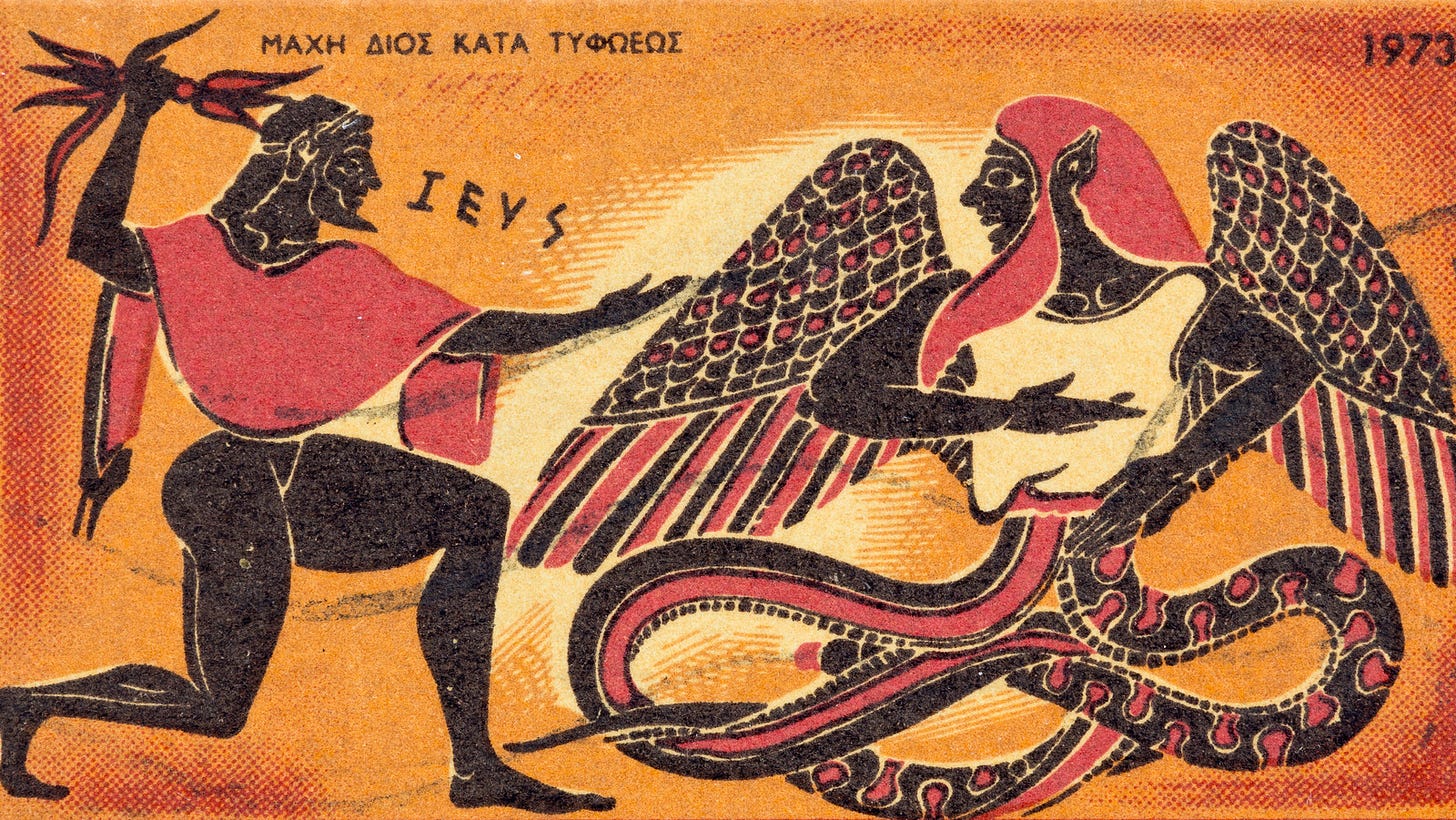

In 2 Peter 2:4 we read that God cast the angels that sinned into hell (KJV) – but the Greek here is neither hades nor gehenna. Rather, it is the word tartarus (Gr. ταρταρόω) which appears only once in the New Testament. According to Greek mythology, tartarus is the great abyss of the earth, the deepest part of hades, the lowest part of the underworld – where Zeus cast Typhon, the son of Gaia and Tartarus according to Hesiod, after their cosmic battle. Elsewhere in Scripture, Jude notes that the angels that rebelled were kept “in everlasting chains (Gr. δεσμοῖς) under darkness (Gr. ζόφος) unto the judgment of the great day” (Jude 1:6, KJV).

THE HARROWING OF HADES:

In the Orthodox Church we tend to call Christ’s descent into hades The Harrowing of Hades as phraseology reflects the notion of a victorious pillaging.

In Scripture:

Scripture teaches Christ’s descent in several distinct passages: the story of Jonah in the belly of the whale prefigures Christ’s descent into the “heart of the earth” (Matthew 12:40); Paul writes that Christ’s ascension implies that he first descended into the “lower parts of the earth” (Ephesians 4:9); Peter tells us that Christ “preached to the spirits in prison” (1 Peter 3:19) – and elsewhere notes that “the gospel was preached to those who are dead” (1 Peter 4:6).

In Early Christian thought:

Early Christian documents likewise attest to Christ’s descent. As early as c. 180 A.D., Irenaeus of Lyons directly connects 1 Peter 3:19–20 with Christ’s descent into hades: “the Lord descended into the regions beneath the earth, preaching His advent there also, and [declaring] the remission of sins received by those who believe in Him”(Against Heresies, 4.27.2). According to Irenaeus, the purpose for this descent was for the salvation of the dead (The Demonstration of the Apostolic Preaching, 7). Around the same time (c. 180s A.D.), St. Melito of Sardis proclaimed that “[Christ] appeared to the dead in hades” (On Pascha, extant fragment).5 Fourth century Saints Cyril of Jerusalem, Hilary of Poitiers, Gregory the Theologian, Ambrose of Milan, Augustine of Hippo, and many others would likewise follow suit.6 This would would later be reflected by Apostles Creed (c. 340 A.D.), which notes that after Christ’s death and burial he “descended to hades.”

In Orthodox hymnography:

Metropolitan Hilarion Alfeyev points out that Christ’s descent into hades is mentioned more than fifty times at the services of Holy Friday and Holy Saturday.7 This is noteworthy because the liturgical texts of the Church were composed between the 7th and 9th centuries A.D. – and bear as its authors several Saints of the Church: St. Ramonos the Melodist (6th century), St. Sophronious of Jerusalem (7th century), St. Andrew of Crete (7th/8th century), St. John of Damascus (8th century), et al.8

Given that the Church’s worship is dogma expressed poetically (lex orandi, lex credendi), it cannot be denied that Christ’s descent into hades is a key tenet of the Orthodox Faith.

In Orthodox Theology & Worship:

Christ’s descent into hades is an event that is heralded as a great victory in the Orthodox Church. As we read in 1 Corinthians 15:55, where Paul quotes Hosea 13:14: “Where, O death, is your victory Where, O grave (hades), is your sting?” And it is with this cry of victory on our lips that we arrive at Church Holy Saturday evening. In expectation we sing, Christ is Risen from the Dead, trampling down death by death, and upon those in the tombs bestowing life (Paschal Troparion) as we process around the Church thrice. Stopping in front of the Church, the presiding priest (who in office and in liturgical typology represents Christ) pounds at the door exclaiming: “lift up your gates, ye princes, and be ye lifted up, ye everlasting doors; and the King of Glory shall enter.” The gatekeeper responds: “Who is this King of Glory?” To which the priest says: “The Lord strong and might. The Lord mighty in battle). This exchange (Psalm 24:7–10) happens thrice, after which the doors are flung open and the faithful, led by the priest, enter into the Church (which represents the Kingdom of God).

This powerful exchange is perhaps one of the most striking of the paschal service. Indeed, death is swallowed up in victory (1 Corinthians 15:54 referencing Isaiah 25:8) for Christ is risen.

CHRIST’S DESCENT INTO HADES: THE MEANING FOR US TODAY

Death is the ultimate enemy of fallen man (1 Corinthians 15:24–26). The descent of Christ into hades represents his victory over death, the harrowing of hades, at which point he flings open the doors to the Kingdom. This is precisely why Paul would say “if there is no resurrection of the dead…your faith is in vain” (1 Corinthians 15":14). The resurrection of Christ, the defeat of death, is the principle dogma of the Church; it is the source of her joy – joy that can withstand even the pangs of suffering, of death before death, and on which account Paul can say, “for me to live is Christ, and to die is gain” (Philippians 1:21).

In Sum:

Without Christ’s harrowing of hades there is no resurrection. Indeed, it is the climax of the entire narrative as it is followed by his bodily resurrection and his ascension. For death could not hold him (Acts 2:24) and now cannot hold those who are in him (Galatians 3:26–28; Mark 8:34; Luke 9:23; John 6:56, et al). Likewise, those who preached to (preceded in preaching by the forerunner (Matthew 14) and accepted the gospel were freed from the prison of death.

This is the answer of the often asked, “What happened to those who died before Christ’s salvific work?” While there would be some disagreement from patristic writers as to who was freed from hades (some would say only the righteous, others would say everyone) the fact remains that all are raised from the dead (called the general resurrection) and undergo the final judgment in body and soul.9

There is yet another symbol that we can take from Christ’s descent: he not only willingly became incarnate and died a horrific death – he pursued us even to the depths of the grave, to hades. And this grave exists not just after death but in the darkness of our own hearts, when we experience hell today. Christ descends into it, willingly, with us, to lead us. But unlike Orpheus of old, Christ is successful in saving his beloved.

Our challenge as we seek to live this reality is to call upon him, like the Psalmist, in our joy and in our distress. To cry that he harken to us in our pain. And insofar as we take his hand, like Adam and Eve above, he will save us.

If you appreciate this article or any others posted here, would you please join as a paid member to support articles in the future?

Or gift a subscription to a friend or donate a subscription to someone who cannot afford it?

I can’t really remember but I want to say most Good Friday services in the church of my youth featured communion. Communion services were distinct from “regular” Sunday services though – and we only celebrated communion about four times total each year.

Recent scholarship has called into question the idea that the valley of hinnom was a place of perpetually burning garbage in Christ’s day. That said, it was certainly a place of the ritualistic burning of sacrificial offerings (typically children) to moloch.

Orthodox Prayer for the Departed.

See How Our Departed Ones Live by Monk Mitrophan.

See fragment 8b, 4. Popular Patristics Series, On Pascha by Melito of Sardis, p. 75.

St. Cyril of Jerusalem, Catechetical Lectures, 4.11; 14.18; St. Hilary of Poitiers, On the Trinity, 10.34; St. Gregory the Theologian, Second Oration on Easter (Or. 45.24); St. Ambrose of Milan, On the Christian Faith, 3.4.28; 3.14.111; St. Augustine of Hippo, Letter 164.2, et al. For a detailed study of first source material on this subject, see Christ the Conqueror of Hell by Metropolitan Hilarion Alfeyev.

Metropolitan Hilarion Alfeyev, Christ the Conqueror of Hell, p. 155.

See Alfeyev, pp. 155–156 for a complete list.

For more on this, see Alfeyev.